the project that introduced me to graph theory

Between 1998 and 2000, while at the USC Information Sciences Institute, I worked in reconfigurable robots, in the Conro project. The P.I. of the project, Peter Will, had the idea of building many small robotic modules that, by themselves, would not do much but, when connected to each other, would coordinate their motions and do interesting things. The modules would not only coordinate their motions to adapt to the shape they found themselves being part of, but they would do this on the fly, and they would change shape themselves. This idea was similar to the Yokai modular robot in Disney’s Big Hero 6 movie, released much later, in 2014; the Yokai had millions of modules while ours had only 20, but our modules were real and they actually worked.

Each of our modules was a little robot composed of a front piece that could swing horizontally, a middle piece that house a tiny computer, and a back piece that could swing vertically. In the videos below we will often see the modules tethered to a harness that provided them power because, although each module had its own batteries and could work with their own power, they went through batteries like candies; hence, we used a power harness during development and saved the batteries for demonstrations. Also, remember the movies are from 1998, so they are already showing their age.

The front piece of each module could connect to the back piece of up to three other modules; ‘composite’ robots were simply a number of modules connected to each other in various configurations. Our configurations were mostly planar; the ones that we worked the most with were snakes, T-shapes, quadrupeds and hexapods. Each configuration had a different locomotion strategy; the snake either could advance moving up and down, like a sine wave, or moving sideways, like a sidewinder; the T-shapes would swing their arms, similar to a butterfly stroke, pushing or dragging the rest of the body; and the quadrupeds and hexapods would use the expected gaits, alternating legs from each side of the body.

The modules were constantly verifying the configuration that they were in. We would just connect the modules to each other and each module would figure out, on its own, both the configuration that they were forming, e.g., a hexapod, and the role it was playing, e.g., the front left leg. Once each module figured out the configuration that it was a part of, and its function as part of this robot, it would then coordinate its own movement with that of its neighbors. We could manually change the configuration on-the-fly, e.g., from snake to quadruped, at which time the modules had to figure out the new configuration on their own, their new role, and then change their movements to enable the new gait accordingly.

Although the robot could change on its own between a few configurations, the heads and tails of the modules did not have the turn radius or strength to change between arbitrary configurations; in the video below, the modules change from a snake configuration to a T-shape one, then identify it, and adapt the gait to a butterfly stroke.

I was in charge of the hardware design – mechanical construction and electronics – and the low level software of these little modules; my job was to design and build the modules, and set up the necessary low-level software so that Wei-min Shen and his students could run more advanced control strategies. My team was a machinist – Bob Kovak, and grad students – Ramesh Chokkalingam, Arvind Seshadri, and Sunan. We were happy to have all the 20 working modules built in a single year; for us, the second year went mostly into maintenance and paper publishing. I moved to JPL in 2000, but the polymorphic robotics lab that this project got started is still going to this day, in 2025.

The graph theory component

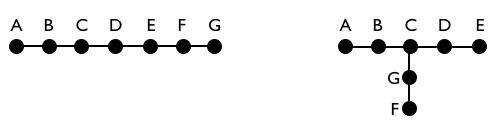

Let’s look at the last video, where a 7-module snake reconfigures itself into a T-shape. If we represent each module as a labeled dot, and the connection between modules as lines, we end up with a graph. Let’s say we design and hardwire the gaits for a 7-module snake and a 7-module T-shape; in each case, we name the modules with letters. For example, for the butterfly gait of the T-shape, we can program that modules A, E, G and F never move while modules B and C need to ‘stroke” simultaneously. Now, if we know that a 7-module shape is either a snake or a T-shape, we can get them to move appropriately.

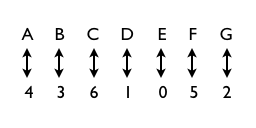

In practice, though, our modules have an identification number, e.g., an ID from 0 to 19; however, we did not know in advance which module would end up in what position. For example, we could assemble the 7-module snake connecting any seven modules in any order, and when the robot changed its configuration to a T-shape, the modules would also end up at unknown locations. In general we have 20!/(7!13!) = 77520 possible different configurations of 7-module T-shapes.

Each little module could talk to the modules attached to it, so each of them could eventually figure out the overall topology, e.g., module 4 is connected to module 3, module 6 is connected to modules 1, 2 and 3, and so on. With this information, it is easy to determine if the 7-module robot is a snake or a T-shape. Each possible configuration would have some ‘features’ that makes them different from the other shapes. For example, all snakes would have exactly 2 modules that are only connected to one module (the end points), while all the other modules are connected to exactly 2 modules; likewise, all T-shapes will have 3 modules that are connected to one module (the end points), one module that is connected to 3 modules (the joint of the T-shape), and all the other modules are connected to exactly 2 modules. We can discover the topology (i.e., the shape) of each possible configuration – of quadrupeds, hexapods, loops, etc. – in a similar way.

After identifying the topology of the robot, we need to map the IDs of each module, which are identified with numbers, to the modules of the abstract shape on which we designed the gaits, which are identified with letters. The name of the mathematical problem that maps the labels of one instance of a graph to the labels of a second instance of the graph while preserving adjacency is called the graph isomorphism (GI) problem. The adjacency preservation statement means that the modules in one graph are connected in the same way as in the other graph. For example, module 6 of the T-shape can be mapped only to module C of the base T-shape because those that the only two modules in their respective graphs that are connected to 3 graphs, i.e., mapping 6 to C is the only way to preserve the adjacency.

The above pairing maps our abstract and practical snake and T-shape configurations, but in this case there are others equally valid mappings; for example, for the snake, instead of mapping modules A and 4, B and 3, and so on, which maps the snakes from heads to tails, we could have mapped modules A and 2, B and 5, and so on, which maps the head of one snake with the tail of the other; in both cases the adjacency is preserved, so both mappings are correct.

In general, in the graph isomorphism problem, we are given two graphs and we have to figure out whether the two graphs are actually the same graph, just with different labels. Our problem was simpler than graph isomorphism because we already knew that the two graphs were the same, i.e., we did not have to solve the graph isomorphism problem, which is fortunate because it is an open problem. Unfortunatelly, well after solving our toy problem and moving on, I had gotten the graph isomophism disease so I kept working on it from time to time. The graph isomorphism problem is easy to understand, even without any math background; what could be easier: see if we can reposition the dots of a graph to match those of a second graph while preserving the adjacency.

The following pages are very much a work in progress. We start by going over the basics of graphs, which is material that we can get from any book on introduction to graph theory, and then we discuss the graph isomorphism problem and some of the problems related to it. I already wrote many of the pages and will slowly make them public; there are things to edit, images to create, theorems to prove, and I have many other projects in the oven; the names of the pages that are not public end in a lock (🔒).

First published on Dec. 17/2025