What’s in a name? That which we call a graph…

Would you like to know more?

Graph theory is the area of math that studies graphs, which are objects composed of a non-empty set of points called vertices, and a set of connections between those points; one-direction connections between vertices, represented by arrows, are called arcs, while two-directional ones, represented by segments, are called edges. An undirected graph has only edges, a directed graph, a.k.a. digraph, has only arcs, and a mixed graph has both.

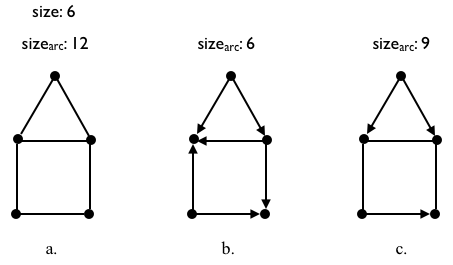

Under the hood, undirected graphs are digraphs because an edge is the same as two arcs traveling in opposite directions; hence, we could recast any undirected graph as a digraph:

We define the order of a graph as the number of vertices of the graph. The size of an undirected graph is the number of edges it has, but this definition leaves the size of digraphs in uncertain ground; given that we can always replace an edge with two opposite pointing arcs, it makes sense to define the sizearc of any graph – directed, undirected and mixed – as the number of arcs it has; hence, if we need the traditional size of graph because we are working with undirected graphs, we divide sizearc by 2. For example, all following graphs have the same order of \(n=5\) but their sizes vary:

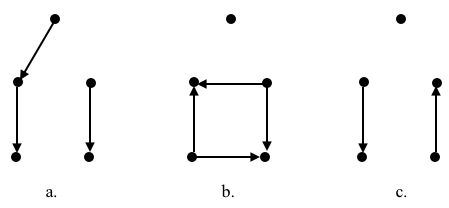

Any subset of a graph is called a subgraph. One characteristic of a graph is based on whether we can reach a given vertex from any another vertex. A graph is connected if we can either depart or arrive to any vertex from any other vertex; if we can’t, then the graph is disconnected. Digraphs that are connected this way are also called strongly connected. The separete subgraphs of a disconnected graph are called components; a single vertex that is a component is called an isolated vertex.

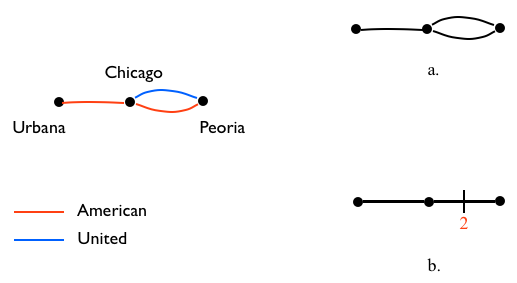

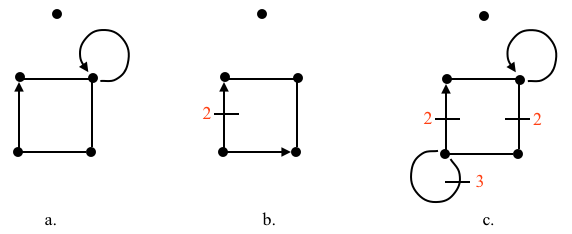

A graph is simple if it has a single edge or arc between any two vertices, like all the graphs above. There are cases where there is a redundant connection between vertices that we can naturally represent with multiple edges between the same two vertices, as it happens when representing non-stop flight routes. For example, we can fly between Chicago and Urbana via American, or between Chicago and Peoria via American or United, but there are no direct routes between Urbana and Peoria. We represent the routes with edges because each route denotes to-and-fro flights, e.g., if there is a flight from Chicago to Urbana, then there is a corresponding flight from Urbana to Chicago. Hence, we can replace each edge with two oposite arcs and we can see all 6 flights. Graphs with multiple edges between two vertices are called multigraphs. We can represent the multiple edges by explicitly drawing them, or by indicating the multiplicity with a numbered tick mark.

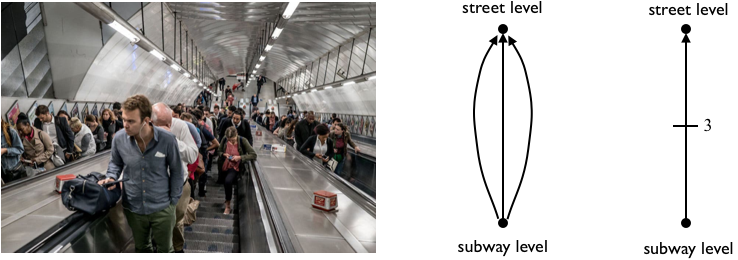

By the same token, digraphs that have multiple arcs between two vertices are called multidigraphs. An example of such a graph would be the representation of the many parallel ascending escalators (arcs) that take people from the subway platform level to the street level in a subway station.

Yet another characteristic of some graphs are loops, a.k.a. self-loops or buckles, which are connections from a vertex to itself. This would be the case, for example, of the platform of a ferris wheel, i.e., we climb a gondola that takes us directly to… the same platform of the ferris wheel. These loops can be arcs (a normal ferris wheel) but could be edges (a ferris wheel that could rotate in either direction). Likewise, there might be cases where we have multiple loops.

Simple graphs don’t have multiple edges or loops; a graph that allows them is called a pseudograph; hence, a multigraph is a pseudograph without loops.

So what is a “graph”? All of the above are graphs! When we read an academic paper on graphs, usually we find early in the text a note that makes clear what type of graphs the author is working with. Theoretical research tends to concentrate on simple connected undirected graphs, while more applied work, like molecule classification or modeling of networks, requires the use of graphs with more characteristics. Following with that tradition:

Unless stated otherwise, our graphs are pseudographs, i.e., our graphs can be directed, indirected or mixed, connected or not, and with loops and/or multiple connections.

First published on Dec. 18/2025