Vocabulary

English

place

where?

where at?

time; hour; o’clock

when?

now

after, later

afterwards

cola, soda

romaji

tokoro

doko?

doko de?

ji

itsu

ima

ato

ato de

koura

kana

ところ

どこ?

どこで?

じ

いつ

いま

あと

あとで

コーラ

- Words like ‘koura’ (cola), borrowed from other languages, are called ‘gai-rai-go’ (外来語, lit. outside-coming-language). With few exceptions, gai-rai-go words are written in katakana and don’t have kanjis. An example of an exception is ‘ei’ (Britain) whose kanji is 英.

Sample sentences

When are you eating? I’ll eat later.

formal

itsu tabe-masu ka? ato de tabe-masu.

いつ たべますか。あとで たべます。

casual

itsu taberu? ato de.

いつ たべる? あとで。

Comments

The following comments explain some of the grammar in more detail.

Particles

no – の

In English, we can say that something belongs to someone in two ways, e.g., “the car of Hana” and “Hana’s car”; other languages are not so flexible, e.g., in Spanish we can only say “the car of Hana”, while in Japanese we can only say “Hana’s car”. In Japanese, one of the most common roles of the particle の is to play the role of this possessive apostrophe, i.e., of ‘s:

English

Hana‘s car

It’s Hana‘s

Hana‘s mother

Hana‘s mother‘s car

Today‘s newspaper

Tomorrow‘s weather

日本語

花の車

花のです

花のおかあさん

花のおかあさんの車

きょうのしんぶん

あしたの天気

This extends to cases wth possessive pronouns in which we don’t usually use aposthrophes but, logically, we could:

English

My dog

It’s mine

Your book

It’s yours

‘logical’ English

I‘s dog

It’s I‘s

You‘s book

It’s you‘s

日本語

私の犬

私のです

あなたの本

あなたのです

Usually, a particle forms a unit only with the word that it precedes, e.g., ‘to Nara’ is ‘ならへ’, ‘in January’ is ‘一月に’, ‘with Hana’ is ’花と’, etc; we can move these units around in the sentence:

English

(In January), I’m going (to Nara) (with Hana)

I’m going (to Nara) (with Hana) (in January)

(To Nara), (in January), I’m going (with Hana)

日本語

(一月に) (ならへ) (花と) いきます

(ならへ) (花と) (一月に) いきます

(ならへ) (一月に) (花と) いきます

English

I’m going (to Nara) (in [Hana‘s car])

I’m going (in [Hana‘s car]) (to Nara)

I’m going (to Nara) (in [[Hana‘s mom]‘s car])

I’m going (in [[Hana‘s mom]‘s car]) (to Nara)

日本語

(ならへ) ([花の車]て) いきます

([花の車]て) (ならへ) いきます

(ならへ) ([[花のおかあさん]の車]て) いきます

([[花のおかあさん]の車]て) (ならへ) いきます

mo – も

‘mo’ (も) means ‘also’, in both positive and negative contexts.

We can translate it as ‘as well’ or ‘too’ in a positive context:

I am going to drink a cola.

Me too.

koura wo nomi-masu.

watashi mo.

and translate it as ‘neither’ in a negative context:

I am not going to drink a cola.

Me neither.

koura wo nomi-masen.

watashi mo.

de – で

‘de’ (で) is ‘at’ when we refer to time:

ato de

ato de nomi-masu

at a later moment (afterwards, later)

I’ll drink at a later moment (I’ll drink later)

or ‘at’ a location where an action takes place.

resutoran de

resutoran de nomi-masu

at the restaurant (something will happen)

I’ll drink at the restaurant

wo – を

‘wo’ (を) marks the direct object of a verb, i.e., the object on which the verb acts. In spite that it is written as ‘wo’, it is often pronounced ‘o’.

English

I drink cola

I eat sushi

romaji

koura wo nomi-masu

sushi wo tabe-masu

kana

コーラを のみます

すしを たべます

When we answer a question, we can replace the ‘question word’ marked with ‘wo’ with our answer. However, when the answer is ‘nanika’, we omit the ‘wo’:

English

What will you eat?

I’ll eat sushi.

I’ll eat something.

romaji

nani wo tabe-masu ka?

sushi wo tabe-masu.

nanika tabe-masu. (no ‘wo’)

kana

なにを たべますか。

すしを たべます。

なにか たべあす。

Not every object of a verb is a direct object. For example, ‘sushi’ is the direct object of ‘I eat sushi’, but ‘chopsticks’ is not a direct object in ‘I eat with chopsticks’ (we are not eating the chopsticks), nor ‘resutoran’ is a the direct object of ‘I eat at the restaurant’ (we are not eating the restaurant), so in these cases the verb does not mark the objects with ‘wo’; if we mark them with ‘wo’ we get some strange meanings:

English

I eat sushi

I eat with chopsticks

I eat chopsticks (I find wood tasty)

I eat at the restaurant

I eat the restaurant (I am Godzilla)

romaji

sushi wo tabemasu

hashi de tabemasu

hashi wo tabemasu

resutoran de tabemasu

resutoran wo tabemasu

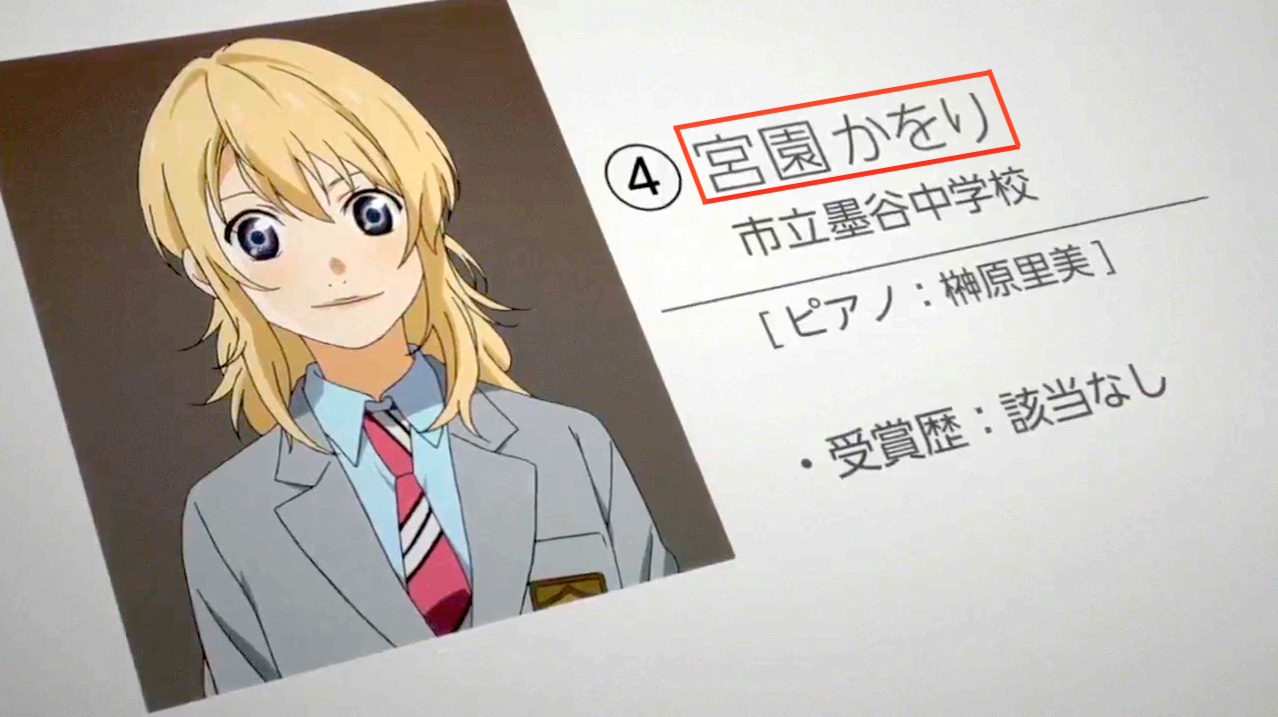

‘wo’ (を) is rarely used to write anything other than the direct object marker. From time to time it appears in an actual word, though. For example, Kawori Miyazono, the character of ‘My lie in April’, spells her name – Kaori (‘scent’), as かをり, instead of using the normal spelling かおり; still, since both お and を are pronounced ‘o’, both spellings sound ‘kaori’:

A common expression where を shows up is 気をつけて (‘ki-wo-tsukete’, ‘take care of yourself’). Here 気 is ‘sprit’ and を is working as the direct object marker of the verb ‘tsukeru’ (‘to attach’), so ‘ki-wo-tsukete’ is a gentle order to ‘attach care to your spirit’, i.e., to ‘take care of yourself’.